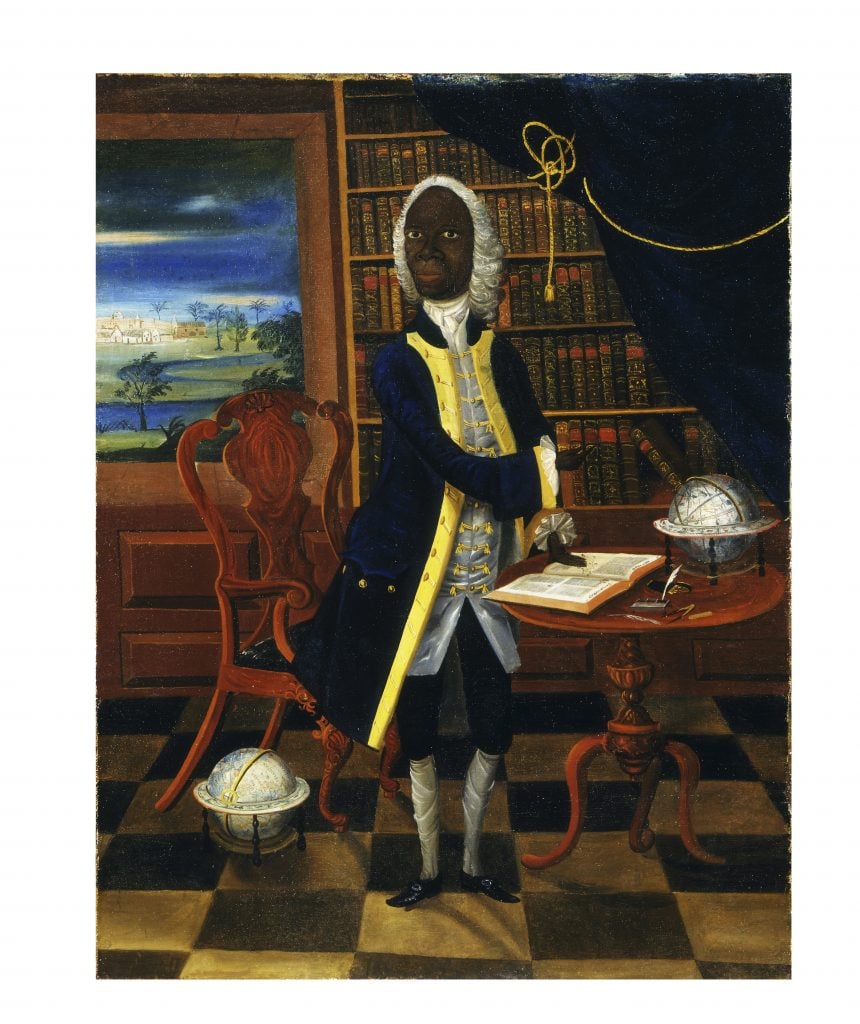

More Light from the Portrait of Francis Williams

Earlier in the month I reported on Fara Dabhoiwala’s work on the portrait of Francis Williams based on two news articles.

I’ve now read Prof. Dabhoiwala’s own article in the London Review of Books, and he has even more to say.

About the painter:

I’ve now read Prof. Dabhoiwala’s own article in the London Review of Books, and he has even more to say.

About the painter:

The only oil painter known to have been active in Jamaica during these years was an Anglo-American artist called William Williams, who was then in his early thirties. This Williams, the son of an ordinary mariner, had been born in Bristol in 1727. He’d always loved to draw. Sent to sea as a youth, he abandoned his crew in Virginia and spent a few years knocking around the West Indies and Central America, sometimes living among Indians, learning their language and trying his luck as a painter for the local colonists.Dabhoiwala also posits that the painting depicts not only the page in Newton’s Principia showing how to calculate the path of a comet but Halley’s comet itself. I’m not entirely convinced by this because the visual clues aren’t distinct. Then again, neither are comets a lot of the time. And the painter was definitely charting something in that portion of the canvas:

Eventually, around 1747, he ended up in Philadelphia, where he worked for a theatre, painting sets and backdrops, and in a boatyard, painting ships, as well as doing sign-painting and lettering, teaching music, writing poetry and composing what is now regarded as the first American novel.

Though he was entirely self-taught, he also made landscapes and portraits; he collected engravings; he used a camera obscura as a drawing aid; he studied the lives of the great artists and wanted to be one himself. He was the earliest teacher of the young Benjamin West, who…in the 1770s commemorated his old mentor by including his likeness in one of his monumental historical canvases.

William Williams kept a list of every painting he ever made. The original doesn’t survive, but in the 19th century someone jotted down a summary of it. In the spring of 1760, Williams travelled from Philadelphia to Jamaica to offer his services as an artist. His list recorded that during his months in Jamaica, he painted 54 pictures. None of these has ever been found. I am confident that the portrait of Francis Williams is one of them.

There is in fact a scientific test that could prove this, because it has recently been discovered that William Williams prepared his canvases with a distinctive and very unusual triple layer of underpainting. I’m pressing the V&A [Victoria & Albert Museum] to undertake this new test as soon as possible.

We can see that on the infrared scans of the picture. When William Williams made his first pencilled marks on this canvas, to plot the composition, he carefully ruled a series of lines to show where that white object in the sky should go – and to mark its relation to the constellations he was told to paint below. His sitter made sure of that, as he made sure of every other carefully placed detail in his portrait.

The portrait of Francis Williams is the only painting ever made of Halley’s comet in 1759, on its momentous first predicted return.

No comments:

Post a Comment