How Shipping Speeds Rose in the 1780s

The Center for Economic and Policy Research’s VOX portal has just published Morgan Kelly and Cormac Ó Gráda’s précis of a study titled “Speed under Sail During the Early Industrial Revolution”.

The authors say:

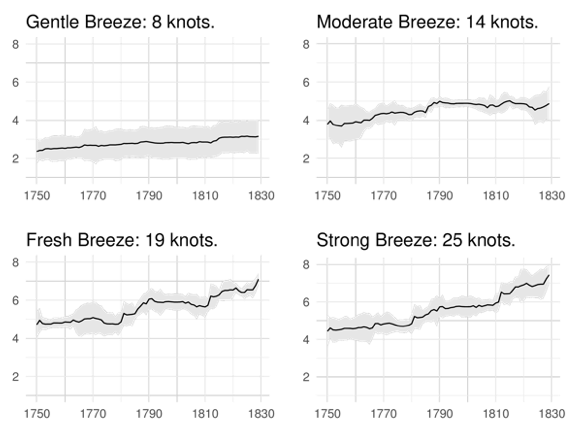

The consensus among economic (but not maritime) historians that maritime technology was more or less stagnant for 300 years until iron steamships appeared in the mid-19th century is largely based on indirect measures, such as changes in the cost of shipping freight or the length of voyages. This column instead looks directly at how the speed of ships in different winds improved over time. . . .Here, for example, are the results for British East India Company ships at different reported wind speeds in the eighty years following 1750. There’s a noticeable rise at higher speeds in the 1780s and another after 1810.

We can do this thanks to an ambitious, but abortive, climatological project called CLIWOC (Wheeler et al. 2006). This attempted to reconstruct oceanic climate conditions between 1750 and 1850 by collecting records from 280,000 log book entries from British, Dutch, and Spanish ships. These give daily information on the ship’s location, wind speed, and direction that allow us to estimate how fast a ship sailed on a given day.

The article continues:

What explains these substantial improvements in British ships? The jump in the 1780s is due to the copper plating of hulls which stopped fouling with weed and barnacles, and over the entire period there were continuous improvements in sails and rigging. A big contribution after 1790 came from the increasing use of iron joints and bolts instead of wooden ones (as well as replacing traditional stepped decks with flat ones fitted with watertight hatches) which made for structurally sounder ships that could safely set more sail, especially in stronger winds.The posting also has maps aggregating all the East India Company and Royal Navy voyages from 1751 to 1790 into pretty blue swirls.

3 comments:

Thanks, this is good stuff. This is complementary detail for the context of travel in the 19th century.

Very interesting, but I wonder about some of the details. For example, I don't understand the reference to stepped decks vs. continuous decks. Earlier ships had bow and stern superstructures that disappeared in the 19th century, but they still had continuous main decks that provided structural strength.

Another explanation for the speed increase might simply be that ships got bigger. The maximum theoretical speed of a sailing ship is proportional to its waterline length. All things being equal, a larger ship is faster than a smaller one, and has more sail area as well.

The increases shown on the graphs are not as dramatic as they look at first sight. Even in the strongest winds, the difference is only 3+ knots. The ships we're talking about (especially the EIC ships) were not designed to go fast, but to be sturdy and rugged enough to make long passages. It would be interesting to see similar data for voyages between, say Europe and North America.

The overall study used data from many voyages beyond those of the British East India Company, which provide the data for the graph. The article states that that company’s ships indeed “sailed slowly.” Nonetheless, if they increased speed by 3 knots over all those long voyages with expensive cargoes, that would presumably have made a noticeable economic impact.

The article summary doesn’t say "continuous decks,” but the reference to replacing “traditional stepped decks with flat ones” seems to mean the flush deck that the East India Company picked up in Asia. Here’s another paper by the same authors focusing on technological change and safety.

Post a Comment