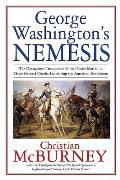

McBurney on “George Washington’s Nemesis,” 8 Oct.

On Thursday, 8 October, the Fraunces Tavern Museum in New York will share a talk by Christian McBurney on “George Washington’s Nemesis: The Outrageous Treason and Unfair Court-Martial of General Charles Lee.”

The event description says:

Lee was paradoxical—a long-serving British officer fighting the British army, one of the most vocal and enthusiastic proponents of American resistance and independence in 1774 and 1776, yet dismissed from the Continental Army by the end of 1778.

McBurney’s new book about Lee leans into exploring such paradoxes. On the one hand, the general’s conduct at Monmouth—for which he was court-martialed, expelled from the army, and turned into a villain—is actually quite defensible. But Lee’s cooperation with the British command when he was a prisoner of war in the preceding months, which Americans didn’t learn about until generations afterward, looks like outright treason.

This online talk will begin at 6:30 P.M. on Thursday. Registration for the event will close at noon on that day.

In the meantime, the Journal of the American Revolution has shared an article by McBurney that grew out of his research for the book, as well as his study of Rhode Island. It discusses one of Lee’s subordinates, Col. Henry Jackson of Boston, and what he did at Monmouth. Did he set off the American retreat that forced Lee to withdraw and regroup? Was his action justified?

In his usual thorough fashion, McBurney analyzes the record of the 1779 inquiry into Col. Jackson’s decisions. In July 1778, a month after the Monmouth battle and while the court-martial of Gen. Lee was still going on, sixteen junior officers complained that due to Jackson’s “misconduct, confusion & disobedience of orders,” “many gentlemen of General Washington’s army have freely delivered sentiments unfavorable” to their units.

Continental Army commanders were in no hurry to remove Jackson, however. It wasn’t until April 1779 that the court of inquiry met in Providence under Col. Timothy Bigelow. And that procedure started out by stating that Jackson himself was “thinking his character much injured & his Reputation highly reproached.” So was he now pushing the inquiry to restore his reputation (as other Continental officers did)?

The Jackson trial went on for months. Only five officers of the original sixteen testified, including only one from Jackson’s own regiment. Their testimony described the colonel’s battlefield behavior in positive terms. So what had caused problems? First, Col. Jackson had fatigued his men by marching them too hard. Second—Gen. Lee.

The event description says:

While historians often treat General Charles Lee as an inveterate enemy of George Washington or a great defender of American liberty, author Christian McBurney argues that neither image is wholly accurate. In this lecture, McBurney will discuss his research into a more nuanced understanding of one of the Revolutionary War’s most misunderstood figures.I can’t think of a historian who portrays Charles Lee as “a great defender of American liberty,” though. Certainly we’ve moved past the nineteenth-century treatment of him as a villain for challenging the sainted Washington after the Battle of Monmouth, but even Lee’s most sympathetic biographers don’t deny he was a difficult, ego-driven man.

Lee was paradoxical—a long-serving British officer fighting the British army, one of the most vocal and enthusiastic proponents of American resistance and independence in 1774 and 1776, yet dismissed from the Continental Army by the end of 1778.

McBurney’s new book about Lee leans into exploring such paradoxes. On the one hand, the general’s conduct at Monmouth—for which he was court-martialed, expelled from the army, and turned into a villain—is actually quite defensible. But Lee’s cooperation with the British command when he was a prisoner of war in the preceding months, which Americans didn’t learn about until generations afterward, looks like outright treason.

This online talk will begin at 6:30 P.M. on Thursday. Registration for the event will close at noon on that day.

In the meantime, the Journal of the American Revolution has shared an article by McBurney that grew out of his research for the book, as well as his study of Rhode Island. It discusses one of Lee’s subordinates, Col. Henry Jackson of Boston, and what he did at Monmouth. Did he set off the American retreat that forced Lee to withdraw and regroup? Was his action justified?

In his usual thorough fashion, McBurney analyzes the record of the 1779 inquiry into Col. Jackson’s decisions. In July 1778, a month after the Monmouth battle and while the court-martial of Gen. Lee was still going on, sixteen junior officers complained that due to Jackson’s “misconduct, confusion & disobedience of orders,” “many gentlemen of General Washington’s army have freely delivered sentiments unfavorable” to their units.

Continental Army commanders were in no hurry to remove Jackson, however. It wasn’t until April 1779 that the court of inquiry met in Providence under Col. Timothy Bigelow. And that procedure started out by stating that Jackson himself was “thinking his character much injured & his Reputation highly reproached.” So was he now pushing the inquiry to restore his reputation (as other Continental officers did)?

The Jackson trial went on for months. Only five officers of the original sixteen testified, including only one from Jackson’s own regiment. Their testimony described the colonel’s battlefield behavior in positive terms. So what had caused problems? First, Col. Jackson had fatigued his men by marching them too hard. Second—Gen. Lee.

No comments:

Post a Comment