William Fitzmaurice was born in Dublin in 1737 and grew up in rural southern Ireland. His parents were from aristocratic families, though neither had titles. William’s father John was a grandson of the Earl of Kerry through a younger son, and his mother Anne was daughter of a knight and brother of the first Earl of Shelburne.

Both those titles—Earl of Kerry and Earl of Shelburne—were in the

Irish peerage. The men holding them were entitled to seats in the Irish House of Lords but not the British House of Lords, which covered England, Wales, and Scotland. Even though people in Great Britain addressed Irish peers by their noble titles, they were technically not British lords. I get the sense that British lords could look down on them a bit, but British commoners were supposed to look up.

In 1743, the year William turned six, his father John Fitzmaurice won a seat in the Irish House of Commons, which he held for the next eight years. At that point, in 1751, the status of the family began to change.

First, William’s uncle the Earl of Shelburne died, leaving his extensive property to John Fitzmaurice on the condition that he adopt his wife’s family name, Petty. John Fitzmaurice accepted the name John Petty Fitzmaurice, in later generations hyphenated as Petty-Fitzmaurice to make the alphabetization easier to remember.

Thus, in 1751 William Fitzmaurice, now in his teens, became

William Petty Fitzmaurice.

Later in 1751, the Crown granted John Petty Fitzmaurice two noble titles: Viscount Fitzmaurice and Baron Dunkerton. It was very common for a peer to have subsidiary titles under his main one, moving down the ladder of peerages (duke, marquess, earl, viscount, and baron). Those titles for John Petty Fitzmaurice came in the Irish peerage, and the new viscount became a member of the Irish House of Lords.

Furthermore, in the British aristocratic system, the eldest son and heir of a peer is by courtesy addressed by his father’s second-highest noble title. Thus, in late 1751 William Petty Fitzmaurice became

Lord Dunkerton.

In 1753 the Crown gave Viscount Fitzmaurice a promotion within the Irish peerage by recreating his late brother-in-law’s title of Earl of Shelburne for him. He was thenceforth addressed as Lord Shelburne.

That meant that in 1753 young Lord Dunkerton gained the courtesy title of

Lord Fitzmaurice. That’s how he was addressed when he went off to Oxford University two years later.

As I said before, the Earl of Shelburne wasn’t entitled to a seat in Great Britain’s House of Lords because he was an Irish peer. Likewise, Lord Fitzmaurice, despite being able to use that courtesy title, wasn’t a British peer. As such, they could stand for seats in the

British House of Commons. And that’s what Lord Shelburne did in 1754, winning a seat he held until 1760.

In that year, the Crown gave the Earl of Shelburne a title within the

British peerage: Baron of (Chipping) Wycombe. That moved him out of the British House of Commons into the British House of Lords. People continued to call him Lord Shelburne because, even though the British peerage was more powerful than the Irish peerage, an earldom was more prestigious than a barony.

As for Lord Fitzmaurice, after his years at college he joined the

British army and served under Gen.

James Wolfe in the 20th Regiment of Foot. He saw action at Rochefort, Minden, and Kloster-Kampen. Good service and noble background allowed Fitzmaurice to become a military aide-de-camp to King

George III in 1760, with the rank of colonel. Within the army he was thus

Col. Fitzmaurice. (This rank was controversial since more senior officers were passed over, but it stuck. Furthermore, even though the man stopped being active in the army, he was by protocol promoted to major general in 1765, lieutenant general in 1772, and general in 1783.)

Also in 1760, Lord Fitzmaurice stood for his father’s seat in the British House of Commons and won. The next year he was elected to the Irish House of Commons representing County Kerry. But before he could take those seats, the situation changed again.

In 1761 the Earl of Shelburne died. Lord Fitzmaurice became the

Earl of Shelburne within the Irish peerage and Baron Wycombe within the British peerage. He was no longer eligible to serve in either country’s House of Commons. (His successor in Britain was Col.

Isaac Barré, a political protégé and fellow veteran of Gen. Wolfe’s regiment.)

It was as the

Earl of Shelburne that the former Lord Fitzmaurice, former Lord Dunkerton, former William Petty Fitzmaurice, born William Fitzmaurice, became a player in British-American politics. Prime Minister

George Grenville appointed him First Lord of Trade in 1763, but Shelburne decided to ally with

William Pitt and resigned a few months later. When the

Marquess of Rockingham and Pitt (now Earl of Chatham) formed a government in 1766, Shelburne became Southern Secretary, but was pushed out after two years.

After 1775, Shelburne sided with Chatham, Rockingham, Barré, and others in opposing

Lord North’s war policies. (Lord North was in the House of Commons, not the House of Lords, because his courtesy title came from being son and heir of the Earl of Guilford.) When news of the defeat at

Yorktown arrived, Lord North’s ministry fell and was replaced with a government led by the Marquess of Rockingham. Shelburne was named one of two Secretaries of State—the first Home Secretary, in fact.

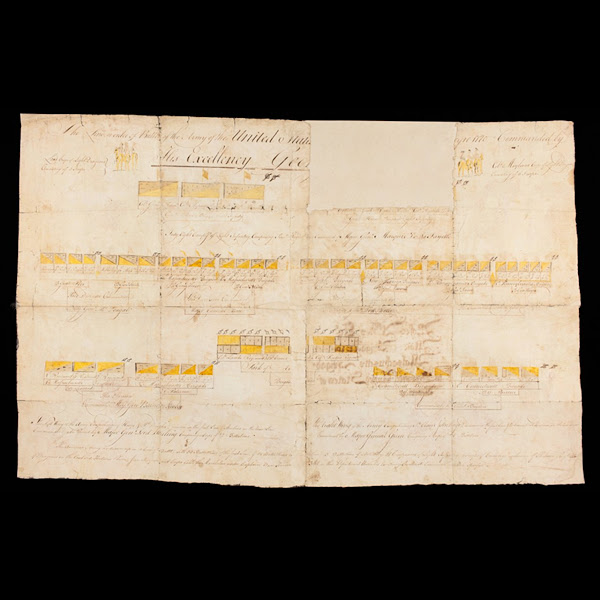

Then Rockingham died after only a few months, and the Earl of Shelburne became Prime Minister in July 1782. He and his envoys handled most of the

negotiations with

France,

Spain, and the U.S. of A. to create the

Treaties of Paris. However, before those documents were signed, Shelburne’s coalition fell because of internal wrangling. Rockingham’s other Secretary of State,

Charles James Fox, made an alliance of convenience with Lord North to oust Shelburne in April 1783.

The next year, young William Pitt the Younger took over the Prime Minister’s office. Rather than bring his father’s old ally Shelburne back into government, he arranged for the man to gain a British peerage higher than his Irish one:

Marquess of Lansdowne. That was the former William Fitzmaurice’s main title from 1784 until his death in 1805.

The marquess stayed out of politics, but he did do something significant in American culture: he commissioned

Gilbert Stuart to create a full-length portrait of

George Washington. Stuart delivered that picture in 1796. The artist also produced copies of what became known as the

“Lansdowne portrait,” including one hung in the White House since 1800. The marquess’s descendants sold the original to the U.S. National Portrait Gallery in 2001 for $20 million.

The seed for this posting was my realization that mentions of Lord Shelburne and Lord Lansdowne in the late 1700s referred to the same man. I started to wonder whether his name and status had changed at other times in his life. I had no idea how complicated the answer would be.

.jpg)