Knox “kept the Sacred image erect”

Given the concatenation of the Fifth of November and yesterday’s discussion of Henry Knox’s childhood, I’ll repeat an anecdote that pertains to both.

On 21 July 1848 a Cambridge man named George Ingersoll sent Charles Daveis, who was trying to write a biography of Knox, a letter setting down a story about the man. Ingersoll said he’d heard the tale from “Mr. Charles Hayward of Boston heard it from the lips of an Eye-witness Mr. Richard Chamberlain, who had been in someway connected with the army” before becoming an import merchant.

Daveis’s papers went into the files of another unsuccessful Knox biographer, Joseph Willard, now at the Massachusetts Historical Society. The anecdote about Pope Night made its way into Francis S. Drake’s 1873 Life and Correspondence of Henry Knox. From there it’s been repeated by every Knox biographer in turn, but I believe this letter is the earliest source.

On 21 July 1848 a Cambridge man named George Ingersoll sent Charles Daveis, who was trying to write a biography of Knox, a letter setting down a story about the man. Ingersoll said he’d heard the tale from “Mr. Charles Hayward of Boston heard it from the lips of an Eye-witness Mr. Richard Chamberlain, who had been in someway connected with the army” before becoming an import merchant.

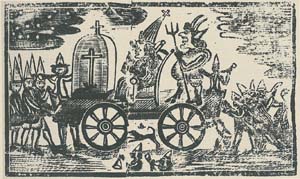

The South & North ends of Boston were, in old times, (that is that exceedgly wise & important [?] portion of the Population the boys) in decided and unceasing opposition to each other. In celebration of that immortal day the fifth of Nov. each Party had its Pope accompanied by the “gentleman in black”—there were thus the South End Pope & the North End Pope.Over the next two years, Daveis collected similar versions of this anecdote from two other men, but no one could say he’d seen the event himself. If this event did happen as described, it was in the late 1760s, when Knox was in his late teens.

These two parties always continued to meet at some half way spot where a regular fight ensued (an annual battle)—which lasted until one Party drove off the other & took possession of its Pope—the victorious Party then took both Popes to some particular place—generally the Mill Pond, & then burnt them both together.

On the present occasion, one of the wheels which supported the Platform of the South End Pope came off—or broke down—this, of course, would tend to Slide off his Holiness into the Street or at least compel him to lower his head before the rival Pope which would be regarded as a Sign of Submission.

To prevent this awful catastrophe, Knox immediately placed his Shoulder under the platform & kept the Sacred image erect until the fight was over. Which way the victory turnd Mr. Hayward does not remember.

Knox at the time was not—properly speaking—a boy, but rather as Mr. Chamberlain said, a dashing young man, about 18 or so. The belligerents—by the way—on these occasions were not by any means mere boys only, but were composed also of young men.

The South End Party was then commanded by a certain Abraham Foley—usually known as Niddy-Noddy, a nickname given him from a peculiar motion of the head. This man afterwards became a Servant and at last died in the Hospital [i.e., was poor and possibly insane]. Knox as Pope man was Subject to his orders—among others of the South End Party. And here, as the Showman says, is the illustration which the anecdote affords—Foley the comander, dying in the Hospital—Knox, the dashing young man, at last the Major-General.

Daveis’s papers went into the files of another unsuccessful Knox biographer, Joseph Willard, now at the Massachusetts Historical Society. The anecdote about Pope Night made its way into Francis S. Drake’s 1873 Life and Correspondence of Henry Knox. From there it’s been repeated by every Knox biographer in turn, but I believe this letter is the earliest source.

No comments:

Post a Comment