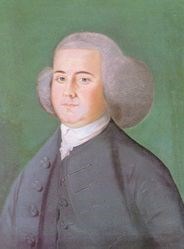

The Rise of John Adams, Boston Lawyer

Between the Liberty riot and the controversy over the Circular Letter, I had to neglect another significant Revolutionary development in June 1768: the entrance of John Adams into Boston politics.

Adams grew up in Braintree and returned to that town to establish his family and legal career. Because of how the Massachusetts Superior Court traveled from county to county, he visited Boston regularly. He had clients there, and he was friends with such significant figures as his cousin Samuel Adams and rising Crown supporter Jonathan Sewall. But for most of the 1760s Adams was a country lawyer, and he liked it that way.

Adams’s earliest public writing was an essay in the 14 Mar 1763 Boston Evening-Post signed “Humphrey Ploughjogger.” Writing in a rustic dialect, Adams lamented the political quarrels in Boston. A second “Ploughjogger” essay said that raising hemp was more important than factional politics. Adams responded to himself in the 18 July Boston Gazette using more genteel language and the new pseudonym “U,” agreeing that agriculture was more productive than arguing in the newspapers.

In August 1765 Adams sent the Gazette a long essay on the history of British law that Edes and Gill printed in installments with no title or signature. When Thomas Hollis republished that essay in London, he titled it A Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law. That work drew Adams closer to the political issues of the day, but he was still viewing them from a distance.

In September 1765 stamped paper arrived in Boston, producing a crisis point. Adams made his first direct contribution to the Patriot political argument by drafting his town’s instructions to its General Court representative to resist the Stamp Act. As toned down by Adams’s neighbors, the “Braintree Instructions” were printed in Boston newspapers. Contrary to what Adams wrote decades later, they didn’t really stand out from or influence the instructions from other towns. But that document did draw Adams into formal politics, and in 1766 he became one of Braintree’s selectmen.

In early 1768, Adams decided to move into Boston to advance his legal career. According to his not-always-reliable autobiography:

The events of June 1768 yanked Adams into Boston politicking. First, on 6 June he was put on a “Committee of the Sons of Liberty” who initiated a correspondence with John Wilkes, the London radical leader.

A few days later came the Liberty seizure and riot. A long town meeting channeled the energy of that uproar into formal political actions. On 15 June, Adams was named to a seven-man committee to instruct Boston’s representatives to the General Court about how to respond. The other members were Dr. Joseph Warren, Richard Dana, Dr. Benjamin Church, John Rowe, Henderson Inches, and Edward Payne. Much later, Adams recalled:

John Adams is credited as the main author of the document that his committee delivered on 17 June. However, he drew on the draft from his cousin’s committee, and his colleagues had input into the final wording of the instructions. Adams later wrote, “there is nothing extraordinary in them of matter or Style, they will sufficiently shew the sense of the Public at that time.” The document protested the Townshend Act, the Liberty seizure, and the impressment of sailors. Boston’s political leaders liked the result enough to ask Adams to draft the next set of instructions in the spring of 1769.

Also in 1768, Hancock, who had known Adams since they were both boys in Braintree, hired him to contest the Liberty seizure in court. It’s not clear when Adams took up that case because the records are spotty. He may have filed Hancock’s first legal responses in July, and he definitely handled the proceedings in Admiralty Court in November. With the Whigs sending one-sided dispatches about the case to newspapers in other ports, the Liberty seizure became a widely reported American grievance, and Adams became one of Boston’s most prominent attorneys.

Adams grew up in Braintree and returned to that town to establish his family and legal career. Because of how the Massachusetts Superior Court traveled from county to county, he visited Boston regularly. He had clients there, and he was friends with such significant figures as his cousin Samuel Adams and rising Crown supporter Jonathan Sewall. But for most of the 1760s Adams was a country lawyer, and he liked it that way.

Adams’s earliest public writing was an essay in the 14 Mar 1763 Boston Evening-Post signed “Humphrey Ploughjogger.” Writing in a rustic dialect, Adams lamented the political quarrels in Boston. A second “Ploughjogger” essay said that raising hemp was more important than factional politics. Adams responded to himself in the 18 July Boston Gazette using more genteel language and the new pseudonym “U,” agreeing that agriculture was more productive than arguing in the newspapers.

In August 1765 Adams sent the Gazette a long essay on the history of British law that Edes and Gill printed in installments with no title or signature. When Thomas Hollis republished that essay in London, he titled it A Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law. That work drew Adams closer to the political issues of the day, but he was still viewing them from a distance.

In September 1765 stamped paper arrived in Boston, producing a crisis point. Adams made his first direct contribution to the Patriot political argument by drafting his town’s instructions to its General Court representative to resist the Stamp Act. As toned down by Adams’s neighbors, the “Braintree Instructions” were printed in Boston newspapers. Contrary to what Adams wrote decades later, they didn’t really stand out from or influence the instructions from other towns. But that document did draw Adams into formal politics, and in 1766 he became one of Braintree’s selectmen.

In early 1768, Adams decided to move into Boston to advance his legal career. According to his not-always-reliable autobiography:

My Friends in Boston, were very urgent with me to remove into Town. I was afraid of my health: but they urged so many Reasons and insisted on it so much that being determined at last to hazard the Experiment, I wrote a Letter to the Town of Braintree declining an Election as one of their Select Men, and removed in a Week or twoHe rented a white house on Brattle Street for himself, Abigail, their two children (Nabby and John Quincy), and servants.

The events of June 1768 yanked Adams into Boston politicking. First, on 6 June he was put on a “Committee of the Sons of Liberty” who initiated a correspondence with John Wilkes, the London radical leader.

A few days later came the Liberty seizure and riot. A long town meeting channeled the energy of that uproar into formal political actions. On 15 June, Adams was named to a seven-man committee to instruct Boston’s representatives to the General Court about how to respond. The other members were Dr. Joseph Warren, Richard Dana, Dr. Benjamin Church, John Rowe, Henderson Inches, and Edward Payne. Much later, Adams recalled:

I was solicited to go to the Town Meetings and harrangue there. This I constantly refused. My Friend Dr. Warren the most frequently urged me to this: My Answer to him always was “That way madness lies.” . . . Although I had never attended a Meeting the Town was pleased to choose me upon their Committee to draw up Instructions to their RepresentativesNow those representatives were:

- James Otis, Jr., moderator of that town meeting.

- Samuel Adams, on a committee that had just drafted a resolution against the Liberty seizure for the town.

- John Hancock, an interested party in the Liberty case.

- Thomas Cushing, speaker of the house and a moderate only by Boston standards.

John Adams is credited as the main author of the document that his committee delivered on 17 June. However, he drew on the draft from his cousin’s committee, and his colleagues had input into the final wording of the instructions. Adams later wrote, “there is nothing extraordinary in them of matter or Style, they will sufficiently shew the sense of the Public at that time.” The document protested the Townshend Act, the Liberty seizure, and the impressment of sailors. Boston’s political leaders liked the result enough to ask Adams to draft the next set of instructions in the spring of 1769.

Also in 1768, Hancock, who had known Adams since they were both boys in Braintree, hired him to contest the Liberty seizure in court. It’s not clear when Adams took up that case because the records are spotty. He may have filed Hancock’s first legal responses in July, and he definitely handled the proceedings in Admiralty Court in November. With the Whigs sending one-sided dispatches about the case to newspapers in other ports, the Liberty seizure became a widely reported American grievance, and Adams became one of Boston’s most prominent attorneys.

No comments:

Post a Comment