How I Spent My Spring Vacation

For the past week I was on a road trip to visit family for the first time in more than two years.

Of course, I also squeezed in some visits to historical archives—my first in-person visits to those archives in even longer.

I was working again on how James McHenry recorded what’s become a famous exchange between Elizabeth Powel and Benjamin Franklin at the end of the Constitutional Convention:

The first question I had to answer on this trip was whether the essays signed “The Mirror” in the Baltimore Republican in 1803 which I attributed to McHenry were indeed his work. I was 95% sure, but I sought certainty in the McHenry Papers at the Library of Congress.

Indeed, those papers contain two drafts of the essays that later appeared in print, complete with the footnotes (which few other newspaper essayists used).

Reading McHenry’s drafts told me little that I didn’t already know from the printed texts. He didn’t, for example, write down the anecdote exactly as he had in 1787 and then cross out crucial words to make it confirm his interpretation.

After the Philadelphia Aurora newspaper dismissed the Franklin anecdote as false, McHenry tried to invoke Powel’s authority as a participant without divulging her name because she was female. He wrestled with how to explain that half-disclosure to readers, as shown by some crossed-out text. But McHenry’s handwriting was sketchy enough that I could make out only the phrase “motives of delicacy.” There’s no indication he wrote out Powel’s name and then removed it.

In 1811 McHenry finally did name Powel as the woman in the anecdote in a pamphlet titled The Three Patriots, Or, the Cause and Cure of Present Evils. I didn’t find a draft of that essay, but an 1876 biography identified it as McHenry’s.

I also visited the Historical Society of Pennsylvania to look at the correspondence of Elizabeth Powel and her family.

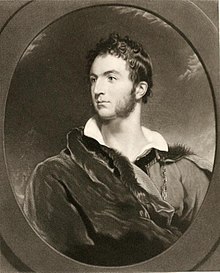

In 1814, that family reacted to what McHenry had said about Elizabeth Powel. Her favorite nephew, John Hare Powel (shown above), wrote to her wondering if the story was true. Powel asked a niece to review that letter with her because the man’s casual handwriting was so bad she wanted to be sure she read it properly. (There are multiple John Hare Powel letters in the archive on which someone has penciled in words that are hard to decipher.) The niece then took down Aunt Elizabeth’s reply, and finally there was a response from John Hare Powel.

I’d already examined Elizabeth Powel’s dictated letter and her nephew’s response, but I wanted to find John Hare Powel’s initial letter about the anecdote—if it survived. That would tell us exactly what story Mrs. Powel was responding to.

I also looked for any document showing James McHenry and John Hare Powel interacting. Powel worked in Baltimore for the Philadelphia militia and U.S. army during the War of 1812, so the two men could well have met, but did they exchange letters? Mention each other? Anything?

Those quests turned up nothing. I wasn’t surprised since David W. Maxey and others have already examined the Powel papers and no doubt looked for the same documents. Nonetheless, I needed to turn over those stones. That meant paging or cranking through the folders of undated and unidentified correspondence in both the McHenry and the Powel Family Papers. I can report that Elizabeth Powel’s handwriting was clear and regular, and that she corresponded with an awful lot of nephews.

Also, I enjoyed John Hare Powel’s carefully written response to another man’s demand:

Of course, I also squeezed in some visits to historical archives—my first in-person visits to those archives in even longer.

I was working again on how James McHenry recorded what’s become a famous exchange between Elizabeth Powel and Benjamin Franklin at the end of the Constitutional Convention:

[Powel:] Well, Doctor what have we got—a republic or a monarchy?And how McHenry used that memory in essays during the early 1800s in a way that changed the story’s implications to fit his political fears. And finally how Powel responded to having her name invoked.

[Franklin:] A republic, if you can keep it.

The first question I had to answer on this trip was whether the essays signed “The Mirror” in the Baltimore Republican in 1803 which I attributed to McHenry were indeed his work. I was 95% sure, but I sought certainty in the McHenry Papers at the Library of Congress.

Indeed, those papers contain two drafts of the essays that later appeared in print, complete with the footnotes (which few other newspaper essayists used).

Reading McHenry’s drafts told me little that I didn’t already know from the printed texts. He didn’t, for example, write down the anecdote exactly as he had in 1787 and then cross out crucial words to make it confirm his interpretation.

After the Philadelphia Aurora newspaper dismissed the Franklin anecdote as false, McHenry tried to invoke Powel’s authority as a participant without divulging her name because she was female. He wrestled with how to explain that half-disclosure to readers, as shown by some crossed-out text. But McHenry’s handwriting was sketchy enough that I could make out only the phrase “motives of delicacy.” There’s no indication he wrote out Powel’s name and then removed it.

In 1811 McHenry finally did name Powel as the woman in the anecdote in a pamphlet titled The Three Patriots, Or, the Cause and Cure of Present Evils. I didn’t find a draft of that essay, but an 1876 biography identified it as McHenry’s.

I also visited the Historical Society of Pennsylvania to look at the correspondence of Elizabeth Powel and her family.

In 1814, that family reacted to what McHenry had said about Elizabeth Powel. Her favorite nephew, John Hare Powel (shown above), wrote to her wondering if the story was true. Powel asked a niece to review that letter with her because the man’s casual handwriting was so bad she wanted to be sure she read it properly. (There are multiple John Hare Powel letters in the archive on which someone has penciled in words that are hard to decipher.) The niece then took down Aunt Elizabeth’s reply, and finally there was a response from John Hare Powel.

I’d already examined Elizabeth Powel’s dictated letter and her nephew’s response, but I wanted to find John Hare Powel’s initial letter about the anecdote—if it survived. That would tell us exactly what story Mrs. Powel was responding to.

I also looked for any document showing James McHenry and John Hare Powel interacting. Powel worked in Baltimore for the Philadelphia militia and U.S. army during the War of 1812, so the two men could well have met, but did they exchange letters? Mention each other? Anything?

Those quests turned up nothing. I wasn’t surprised since David W. Maxey and others have already examined the Powel papers and no doubt looked for the same documents. Nonetheless, I needed to turn over those stones. That meant paging or cranking through the folders of undated and unidentified correspondence in both the McHenry and the Powel Family Papers. I can report that Elizabeth Powel’s handwriting was clear and regular, and that she corresponded with an awful lot of nephews.

Also, I enjoyed John Hare Powel’s carefully written response to another man’s demand:

The voice of your creditors whom you have not paid—the Bills of the Grand jury by whom you were indicted—the books of the Commissioners by whom you were employed—the docket of the Office whence you have been expelled—the facts shown to the Legislature before whom you were arraigned are better evidence of “your standing” than any proofs you could bring if I had either leisure or disposition to engage in the discussion which you have the insolence to propose

No comments:

Post a Comment