“A thoroughgoing refutation of the Whig historians’ estimation of George III”

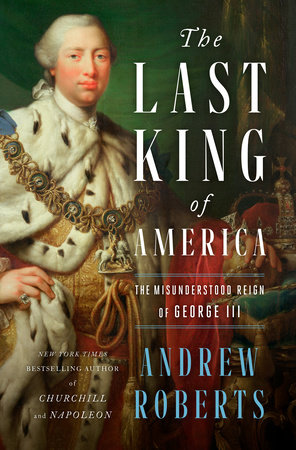

The H-Early-America email list just ran Matthew Reardon’s review (P.D.F. download) of The Last King of America: The Misunderstood Reign of George III by Andrew Roberts.

Like other reviewers, Reardon notes Roberts’s main thesis (especially for U.S. readers): that George III wasn’t a tyrant as American Patriots and many of their descendants portrayed him. He was committed to the eighteenth-century British form of constitutional monarchy. Indeed, his respect for some political traditions limited what measures he endorsed to put down the colonial rebellion.

In addition, this George was personally nicer to his family and circle than his predecessor and successor.

Roberts argues the king’s periods of insanity resulted from bipolar disorder. As to other times, “Far from the dullard regularly portrayed in print and film, George III in fact possessed an inquisitive mind, with interests spanning from astronomy to agriculture.”

Reardon takes issue with how the book treats the American Revolution:

Like other reviewers, Reardon notes Roberts’s main thesis (especially for U.S. readers): that George III wasn’t a tyrant as American Patriots and many of their descendants portrayed him. He was committed to the eighteenth-century British form of constitutional monarchy. Indeed, his respect for some political traditions limited what measures he endorsed to put down the colonial rebellion.

In addition, this George was personally nicer to his family and circle than his predecessor and successor.

Roberts argues the king’s periods of insanity resulted from bipolar disorder. As to other times, “Far from the dullard regularly portrayed in print and film, George III in fact possessed an inquisitive mind, with interests spanning from astronomy to agriculture.”

Reardon takes issue with how the book treats the American Revolution:

Although it is a thoroughgoing refutation of the Whig historians’ estimation of George III, it thoroughly embraces their interpretation of the American Revolution as an inevitable coming-of-age event. Ignored is the recent historiography positing either institutional, ideological, or economic causes for independence, in favor of older arguments associated with salutary neglect.That might be an effect of getting deeply into George III’s head: not seeing how Americans felt just as committed to the British constitution as they understood it, and broke with Britain only after deciding there was no way to heal the rifts between them and their national government and sovereign.

Many historians of early America will certainly take note of bold but unsourced statements such as “by the time of the Peace of Paris of 1763 … some [Americans] were ready for full statehood” or that “many Patriots had indeed long wanted the thirteen colonies to become an independent nation” (pp. 107, 286). Who were these shadowy American revolutionaries quietly waiting (for decades it seems) for an opportunity to break from Britain? None are ever identified.

When evaluating the colonists’ motives for independence, the interpretative slant becomes downright American Tory in its cynicism. Objections to “taxation without representation” were merely disingenuous “proxy protests against British political control by a people who sensed they could now thrive as an independent country,” we are told, while the Declaration’s content is summarily dismissed as “simultaneously grotesquely hypocritical, illogical, mendacious and sublime” (pp. 113, 306).

No comments:

Post a Comment