“In about two Hours the Boy recovered”

But also how earlier that month the Boston Evening-Post had reported that a British diplomat in Portugal saved the life of a drowned Dutch sailor by rubbing him with salt.

Gershom’s father, Joseph Spear, tried the same desperate measure, as reported in detail in the 25 November Boston News-Letter:

The following Account of aRecovery after Drown-Now the Spears didn’t just use salt. They also deployed rubbing, warm blankets, and an enema. And some part of that combination worked.

ing may be depended on, viz.

Boston, November 25. 1762.

On the 21st of this Instant [i.e., of this month], Gershom Spear, a Boy of about 8 Years of Age, Son of Joseph Spear, fell from a Wharf in this Town, near the South-Battery.—

His Father having occasion to remove a Lighter or Boat at High-Water, discovered the Boy under Water, he immediately got up the Body, and carried it into the House a lifeless Corpse; but having heard the Method of recovering drowned Persons with Salt, he directly strip’d the Cloaths off the Boy, and applied a Quantity of fine Salt, which he kept constantly rubbing the Body with, and applying warm Blankets, Help also being obtained, a Glister [clyster] was infused into the Body, when in about 15 Minutes there were feint Signs of Life discovered by a Moving of the Belly and a small Noise in the Bowels, which soon after was following by a Froth issuing from his Mouth:

The Method was continued till the Water discharged itself freely, and in about two Hours the Boy recovered his Senses so as to speak; and in an Hour or two after was able to give an Account of the Manner of his falling in, which, to the Time of his Father’s taking him up, according to the best Computation, was above a Quarter of an Hour:

However that be, the Boy when carried into the House had no Puls, his Neck stiff, and to all Appearance was dead:—

He is now recovered excepting his Feet, which by the Blood settling there has caused a Soreness that prevents his walking.

Little Gershom grew up, became a cooper, married, had several children, and built a successful career in Boston business. But his height of global fame may well have come when the 5-8 Feb 1763 London Chronicle reprinted the story of how he was revived from being a “lifeless corpse.”

TOMORROW: Humane concerns.

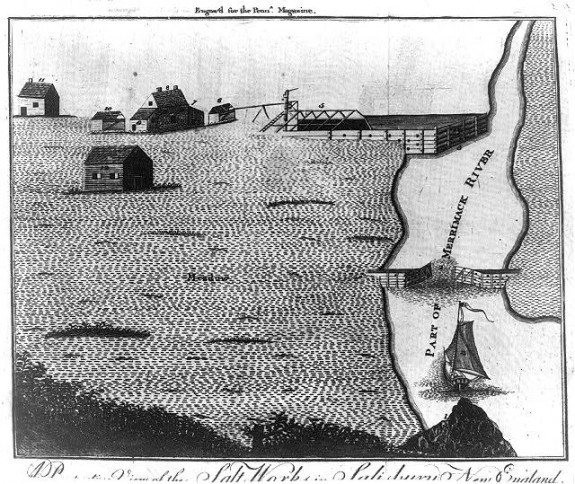

[The engraving above shows the saltworks in Salisbury, New Hampshire, engraved for Robert Aitken’s Pennsylvania Magazine in 1776, courtesy of the Library of Congress.]