“The First BIBLE ever printed in America”?

As I quoted yesterday, Isaiah Thomas grew up as an apprentice printer hearing stories about how his master, Zechariah Fowle, had helped to secretly print a New Testament in the late 1740s.

Thomas also heard about a complete Bible completed by another Boston printing partnership, also surreptitiously, by 1752.

However, it’s worth noting that in his History of Printing in America (1810), Thomas admitted about the New Testament publication, “I have heard that the fact has been disputed.” While he claimed John Hancock had owned a copy of the full Bible, he couldn’t point to any extant examples or describe how they might be recognized.

Indeed, in 1770 another Boston printer publicly denied the existence of any previous American-made Bible. The 3 Dec 1770 Boston Evening-Post included a large advertisement that began:

The printer making this offer was John Fleeming, late of the Boston Chronicle, now working out of “his PRINTING OFFICE, in Newbury-street, nearly opposite the WHITE-HORSE Tavern, Boston.” He had married Alice Church in August and was probably looking for a way to support a family.

The annotator Samuel Clarke (1626-1701) had been a Nonconformist minister in Britain who first published his edition of the Bible in 1690. That book was reprinted in Glasgow in 1765, which is probably how Fleeming, a Scotsman, got the text. The Rev. George Whitefield praised Clarke’s work, and of course Americans widely admired Whitefield. Indeed, almost half of Fleeming’s advertisement was a quotation from Whitefield.

Within the next two months, the same ad appeared in many other New England newspapers and in New York. However, Fleeming must not have collected the subscriptions he hoped for. In modern terms, his Kickstarter campaign failed. That edition was never published.

In 1782 the Philadelphia printer Robert Aitken likewise announced that he would print the first English Bible in America. And he actually completed the job that September. The Continental Congress and George Washington both praised the enterprise. Many copies survive.

Obviously Fleeming and Aitken didn’t acknowledge the editions that Isaiah Thomas had heard about. Thomas would have said that was because the Kneeland and Green Bible, and the Rogers and Fowle New Testament that preceded it, had been disguised as London publications in order to get around a special grant to certain British printers.

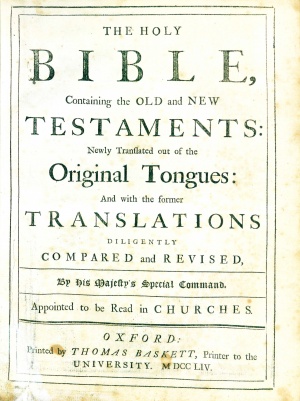

In different writings Thomas specified that the Boston Bible appeared in 1749 and carried the imprint “London: Printed by Mark Baskett, Printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty”—but that man didn’t start publishing Bibles until the 1760s. Was this a mistake for Thomas Baskett, who did issue Bibles in the 1740s? Or is its main significance as evidence that Thomas hadn’t actually seen the Bible he believed did exist?

Many book collectors have searched for the fake Baskett Bible that was actually printed in Boston. Presumably this means finding a Bible with a London Baskett imprint but with typography that didn’t match copies known in Britain.

However, only one candidate for such a book has been found, surfacing in 1895, according to an article in the Boston Globe. Three decades later, Dr. Charles L. Nichols’s close examination showed that was actually a genuine Baskett Bible from 1763 that someone had altered by removing one volume’s title page and clumsily changing the date on the other to 1752. See his findings delivered to the Colonial Society of Massachusetts.

Nonetheless, as Nichols stated in a follow-up paper for the American Antiquarian Society (P.D.F. download), he remained convinced that there was a Bible published surreptitiously in Boston, even if Thomas didn’t have all the details right.

Subsequent scholars, including Randolph C. Adams in The Colophon in 1935 and Harry Miller Lydenberg in the Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America in 1954, were more skeptical. They concluded that Thomas’s report was simply wrong.

Perhaps the digitization of books will produce the anomalous copy of a Baskett Bible that collectors have sought. More likely, however, Zechariah Fowle just lied to little Isaiah about how he’d labored long and hard over a secret publication of the Bible.

Thomas also heard about a complete Bible completed by another Boston printing partnership, also surreptitiously, by 1752.

However, it’s worth noting that in his History of Printing in America (1810), Thomas admitted about the New Testament publication, “I have heard that the fact has been disputed.” While he claimed John Hancock had owned a copy of the full Bible, he couldn’t point to any extant examples or describe how they might be recognized.

Indeed, in 1770 another Boston printer publicly denied the existence of any previous American-made Bible. The 3 Dec 1770 Boston Evening-Post included a large advertisement that began:

The First BIBLE ever printed in America.The following paragraphs promised large and elegant type and paper manufactured in America—or “superfine Imperial Paper” for those few ready to pay double for extra quality. The book was to be delivered in seventy installments of five pages each, starting two weeks after three hundred people had subscribed.

PROPOSALS

For printing by Subscription, in a most beautiful and elegant Manner, in two large Volumes Folio.

The HOLY BIBLE,

Containing the OLD and NEW TESTAMENTS,

Or a FAMILY BIBLE,

With Annotations and Parallel Scriptures.

By the late Rev. SAMUEL CLARK, A.M.

The printer making this offer was John Fleeming, late of the Boston Chronicle, now working out of “his PRINTING OFFICE, in Newbury-street, nearly opposite the WHITE-HORSE Tavern, Boston.” He had married Alice Church in August and was probably looking for a way to support a family.

The annotator Samuel Clarke (1626-1701) had been a Nonconformist minister in Britain who first published his edition of the Bible in 1690. That book was reprinted in Glasgow in 1765, which is probably how Fleeming, a Scotsman, got the text. The Rev. George Whitefield praised Clarke’s work, and of course Americans widely admired Whitefield. Indeed, almost half of Fleeming’s advertisement was a quotation from Whitefield.

Within the next two months, the same ad appeared in many other New England newspapers and in New York. However, Fleeming must not have collected the subscriptions he hoped for. In modern terms, his Kickstarter campaign failed. That edition was never published.

In 1782 the Philadelphia printer Robert Aitken likewise announced that he would print the first English Bible in America. And he actually completed the job that September. The Continental Congress and George Washington both praised the enterprise. Many copies survive.

Obviously Fleeming and Aitken didn’t acknowledge the editions that Isaiah Thomas had heard about. Thomas would have said that was because the Kneeland and Green Bible, and the Rogers and Fowle New Testament that preceded it, had been disguised as London publications in order to get around a special grant to certain British printers.

In different writings Thomas specified that the Boston Bible appeared in 1749 and carried the imprint “London: Printed by Mark Baskett, Printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty”—but that man didn’t start publishing Bibles until the 1760s. Was this a mistake for Thomas Baskett, who did issue Bibles in the 1740s? Or is its main significance as evidence that Thomas hadn’t actually seen the Bible he believed did exist?

Many book collectors have searched for the fake Baskett Bible that was actually printed in Boston. Presumably this means finding a Bible with a London Baskett imprint but with typography that didn’t match copies known in Britain.

However, only one candidate for such a book has been found, surfacing in 1895, according to an article in the Boston Globe. Three decades later, Dr. Charles L. Nichols’s close examination showed that was actually a genuine Baskett Bible from 1763 that someone had altered by removing one volume’s title page and clumsily changing the date on the other to 1752. See his findings delivered to the Colonial Society of Massachusetts.

Nonetheless, as Nichols stated in a follow-up paper for the American Antiquarian Society (P.D.F. download), he remained convinced that there was a Bible published surreptitiously in Boston, even if Thomas didn’t have all the details right.

Subsequent scholars, including Randolph C. Adams in The Colophon in 1935 and Harry Miller Lydenberg in the Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America in 1954, were more skeptical. They concluded that Thomas’s report was simply wrong.

Perhaps the digitization of books will produce the anomalous copy of a Baskett Bible that collectors have sought. More likely, however, Zechariah Fowle just lied to little Isaiah about how he’d labored long and hard over a secret publication of the Bible.

5 comments:

Wasn't the first bible ever printed in America Eliot's translation into the Natick language?

Yes, in the late 1600s New Englanders printed two editions (and a New Testament) of John Eliot’s Bible translation. Isaiah Thomas knew about that, and was careful in his discussion (quoted yesterday) to refer to the book in question here as the first English Bible. But John Fleeming in his 1770 advertisement didn’t make that distinction.

Damn, Adam Gaffin beat me to it. Might he be an alumnus of Roxbury Latin, the school John Eliot founded in 1645?

Dear Mr. Bell, I've been thoroughly enjoying your posts about Boston 1775. I am researching the paper mill which supplied the paper to Benjamin Edes, whose press produced the Mass. Constitution (John Adams version). I have done a lot of searching, and cannot find the source. The Edes Museum in Boston doesn't answer my emails, and they don't have a phone number to call.

Any suggestions?

Thank you, and best wishes, Victoria Worth

Twelve years ago Peter Hopkins was chronicling the early years of the Crane paper company on this website. Among the sources he used was a ledger from the Liberty Paper Mill, a document then owned by Crane.

It’s possible that the Liberty Paper Mill accounts preserve transactions with Benjamin Edes. They do show the Boston printers Isaiah Thomas and Ezekiel & Sarah Russell purchasing paper from that mill.

If Edes’s account books survive, they’d preserve a record of transactions from the other direction. But I don’t recall ever seeing such documents mentioned.

Occasionally newspaper publishers named or alluded to their paper suppliers in the newspapers, but often they had to buy from whatever source they could.

Post a Comment