Charles Pinckney in Hindsight and the Supreme Court

Yesterday I was struck by Pema Levy’s article at Mother Jones about a false document being cited to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Levy based her article on September essay at Politico by Ethen Herenstein and Brian Palmer, and by briefs that have been filed with the court since.

Levy writes:

Advocates for the “Independent State Legislature” theory have seized on one small detail in the post-Constitution Pinckney document, arguing that it shows the Framers (not just Pinckney) planned at the start of the Constitutional Convention (not two to four decades later) to give states unlimited power over federal elections.

Levy says:

The response has been legal tap-dancing:

Levy based her article on September essay at Politico by Ethen Herenstein and Brian Palmer, and by briefs that have been filed with the court since.

Levy writes:

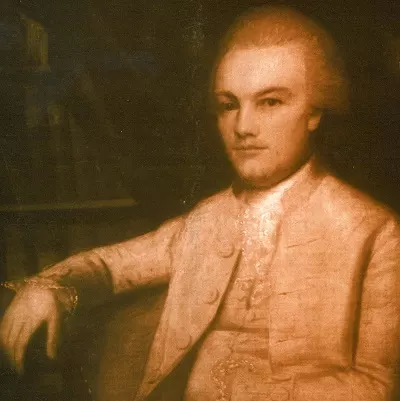

Three decades after the Constitution was drafted in Philadelphia, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams set about assembling the government’s official Journal of the Convention. Missing from the records was the proposal submitted by Charles Pinckney of South Carolina [shown here]. So Adams wrote him to request a copy. Pinckney replied with an extraordinary document: a draft that so closely resembled the final Constitution that he would have to have been clairvoyant to have written it. . . .Max Farrand included the Pinckney document in his comprehensive twentieth-century compilation of documents related to the U.S. Constitution, but with a note and additional documents making quite clear that it was not a reliable historical source. A genuine contemporaneous copy of Pinckney’s actual plan survived in the papers of James Wilson and was published in 1904.

“At the distance of nearly thirty two Years it is impossible for me now to say which of the 4 or 5 draughts I have was the one,” he replied to Adams’ request in 1818, “but enclosed I send you the one I believe was it.” Oddly, the document was written on paper with a 1797 watermark, matching his accompanying letter. Nonetheless, Adams published it.

The debunkings came fast. James Madison, the convention’s most meticulous notetaker, soon wrote to friends that the draft was inaccurate. Years later, Madison discredited Pinckney’s fraud in writing, explaining the document contained language that had only been arrived at after weeks of debate and could not have been divined before the convention began. Madison, convinced it was a fake, detailed how Pinckney’s supposed draft contradicted a more contemporaneous account of the South Carolinian’s actual proposal.

Advocates for the “Independent State Legislature” theory have seized on one small detail in the post-Constitution Pinckney document, arguing that it shows the Framers (not just Pinckney) planned at the start of the Constitutional Convention (not two to four decades later) to give states unlimited power over federal elections.

Levy says:

there is no evidence that the framers of the Constitution intended to give legislatures such authority over federal elections. Nor is there any record this interpretation was accepted in the republic’s early years. In fact, history shows that the independent state legislature theory is a modern invention. . . .Historians and legal scholars, including some on the political right, have filed briefs arguing against reliance on this document in particular and the theory being espoused in general.

It’s possible that the lawyers…who cited the version of the document in Farrand’s 1911 compendium, simply failed to read past the plan to the historian’s conclusion that it was a fake, and that they likewise failed to read Madison’s public takedown or his private letters expressing doubts, all of which were included by Farrand. Whether they meant to or not, they hung their argument on a fake document because it offered a glimmer of originalist evidence to back up their case.

The response has been legal tap-dancing:

the lawyers filed a new brief defending their use of the Pinckney plan. They argued that the plan was not technically “a fake” because it is “undisputed” that Pinckney wrote it, and allege that the generations of historians who discredited the document were hoodwinked by Madison’s “campaign to diminish the significance of [Pinckney’s] role at the convention.”Justices on the Supreme Court today have been willing to deny photographic evidence and ignore decades of legal and historical precedent in order to reach the verdicts they want. In this case, a majority could adopt the “Independent State Legislature” theory without mentioning one problematic document. But if the final decisions do mention Pinckney, that will be yet more evidence that the “originalists” on the court aren’t interested in the original Constitution at all.

No comments:

Post a Comment