“The little bottle of tea came from David Kennison’s pockets”

Moving further west, I arrive at another set of tea leaves linked to the Boston Tea Party, these in the collection of the Chicago History Museum.

They reportedly came from an old New Englander named David Kennison or Kinnison. He arrived in Chicago in the mid-1800s and recounted participating the Tea Party and other celebrated events of the Revolution. For a young but growing western city, he was a link back to America’s beginning.

The problem with that lore is that it’s quite clear David Kennison was a fraud. He exaggerated his age. He claimed people from New Hampshire had traveled all the way to Boston to destroy the tea. He told false and contradictory stories about military service during the Revolutionary War.

Furthermore, authors have debunked Kennison’s claims for over a century now. Every few decades through the 1900s, people rediscovered the same weak points and genuine records. But the artifacts, the original credulous accounts, and the wish for a link to the Boston Tea Party survive. Kennison’s stories therefore keep creeping back into view.

A very thorough examination of the tea leaves linked to Kennison appears at the “Hidden Truths” website. I particularly appreciate the rundown of all public mentions of this tea in Chicago:

The page concludes with the leaves’ most recent public appearance:

I wouldn’t be surprised if the tea at the Chicago Historical Society was always packaged in that souvenir glass chest and people chose to refer to it as a bottle or vial since those seemed like proper terms for a relic of the Boston Tea Party. After all, those same people had also convinced themselves that David Kennison was a reliable storyteller.

They reportedly came from an old New Englander named David Kennison or Kinnison. He arrived in Chicago in the mid-1800s and recounted participating the Tea Party and other celebrated events of the Revolution. For a young but growing western city, he was a link back to America’s beginning.

The problem with that lore is that it’s quite clear David Kennison was a fraud. He exaggerated his age. He claimed people from New Hampshire had traveled all the way to Boston to destroy the tea. He told false and contradictory stories about military service during the Revolutionary War.

Furthermore, authors have debunked Kennison’s claims for over a century now. Every few decades through the 1900s, people rediscovered the same weak points and genuine records. But the artifacts, the original credulous accounts, and the wish for a link to the Boston Tea Party survive. Kennison’s stories therefore keep creeping back into view.

A very thorough examination of the tea leaves linked to Kennison appears at the “Hidden Truths” website. I particularly appreciate the rundown of all public mentions of this tea in Chicago:

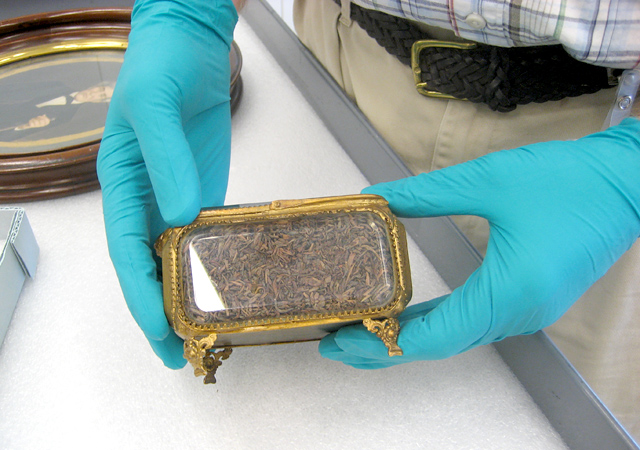

1894: forty-two years after David Kennison's death, news of the existence of tea leaves in the possession of Fernando Jones is published in a Chicago newspaper. Jones mentions the affadavit, and explains the little bottle of tea came from David Kennison’s pockets. The leaves were purportedly left in the possession of Kennison's mother, who kept them in her cupboard until Kennison retreived them years later.The artifact appears above in a photograph made by the Chicago Historical Society for that website.

1901: Fernando Jones has two vials of tea.

1903: Jones's tea leaves came from David Kennison's boot, where they had accidentally fallen during the Boston affair.

1908: Chicago Historical Society acquires photo reproduction of a daguerreotype of Kennison.

1911: Fernando Jones dies.

1912: Chicago Historical Society acquires vial of tea and affadavit declaring its authenticity.

1939: CHS is acknowledged to have a daguerreotype of David Kennison.

1975: CHS has "2 ounce vial of tea sealed with red wax," accompanying affadavit, CHS also has a painting, and pictures of Kennison.

1982: CHS has vial of tea

1987: CHS has golden chest of tea

The page concludes with the leaves’ most recent public appearance:

Chicago History Museum, June 2007, the exhibition, “Is It Real?”I think the references to vials of tea sealed with red wax reflects the strength of the meme established by the Thomas Melvill tea starting in 1821. Relics of the Tea Party packaged or created after that became famous tended to fit the same mold, like the vial the Massachusetts Historical Society gave to Gov. William Seward in 1841. When sealing wax became less common, people resorted to sealing those vials with wooden corks.

For this exhibition, curated by Peter Alter, objects from within the museum’s collection were presented with thoughtful text panels questioning the objects’ claimed significance. . . .

When I inquired about the vial of tea sealed in red wax, he said he had never seen such an item. He showed me the tea leaves. They were contained within the same chest that was pictured in the 1987 “We the People” catalogue. Some time between 1982 and 1987, the vial of tea had become a chest of tea.

But what looks like a full container of tea leaves, is actually a falsely fashioned front containing a very small quantity of tea. In this last Hidden Truth mystery regarding David Kennison, the newer container for the tea leaves, is actually an item from from the 1893 Columbian Exposition. It is a replica of the golden chest that held the ashes of Christopher Columbus.

Peter Alter does not know how the tea ended up in this container.

I wouldn’t be surprised if the tea at the Chicago Historical Society was always packaged in that souvenir glass chest and people chose to refer to it as a bottle or vial since those seemed like proper terms for a relic of the Boston Tea Party. After all, those same people had also convinced themselves that David Kennison was a reliable storyteller.

No comments:

Post a Comment