“Ink of a Very Different Sort”

Anisha Gupta and Renée Wolcott of the conservation department at the American Philosophical Society have shared an interesting series of blog posts about iron gall ink and the problems it can produce.

Iron gall ink has been around at least since the 300s. It offered scribes the advantage of being close to permanent, especially on parchment—but when the formula is off, it can damage that material.

Gupta explained what went into this type of ink:

Iron gall ink was used in quill pens, so it had to flow and then dry. A completely different type of ink was developed for printing.

TOMORROW: Printers’ ink.

Iron gall ink has been around at least since the 300s. It offered scribes the advantage of being close to permanent, especially on parchment—but when the formula is off, it can damage that material.

Gupta explained what went into this type of ink:

Iron gall ink is comprised of four main ingredients:Wolcott highlighted a notebook from Benjamin Franklin’s papers recording his early experimentation (of course) with the substance:

1. Oak gall nuts. Oak gall nuts are a tree’s protective reaction to wasps depositing eggs beneath its bark. They are not actually nuts! Once collected, these are then soaked in a solvent.

2. Solvents. Acidic solvents, such as beer or wine, or allowing mold to grow on the gall nuts as they soak help produce gallic acid and increase the color of the ink.

3. Ferrous sulfate. Ferrous sulfate reacts with gallic acid to produce a blue-black iron-tannin complex.

4. Gum Arabic. Gum Arabic increases viscosity (improves ink flow), keeps pigment particles in suspension, binds ink to the writing surface, and gives the ink shine and depth.

The formation of the iron-tannin complex releases sulfuric acid, so iron gall ink is always extremely acidic, with a pH of 1-3. Acids attack the cellulose chains that paper is made of, shortening the chains and making the paper brown and brittle. If the iron gall ink contains an excess of iron (II) ions, it will also catalyze oxidation of the paper or parchment, which results in crosslinking and brittleness.

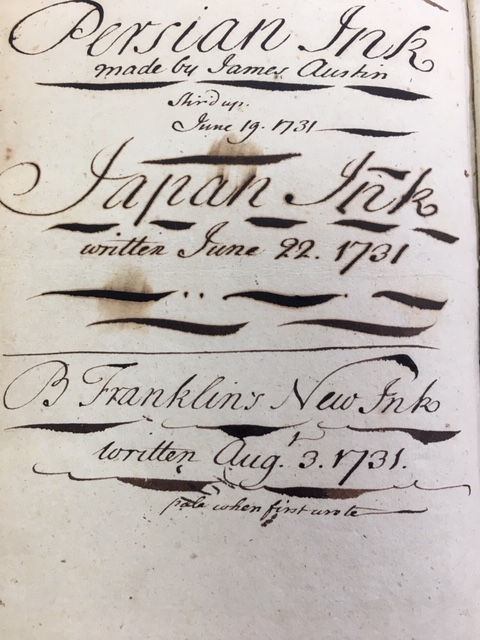

at the very back of the book…Franklin had recorded the results of six iron gall ink recipes, including “Benj. Franklin’s Ink” from June 17, 1731, “Joseph Breitnall’s Ink” and “Ink of a Very Different Sort” from the same date. (Oh, how I wish I knew what made the different ink different!)Finally, Wolcott showed an example of damage caused by iron gall ink that was too acidic for its paper.

“Persian Ink made by James Austin” was “stir’d up June 19, 1731.” The “Japan Ink written June 22, 1731” was likely made from a commercial ink powder that could be mixed with water, and it has aged the most poorly, with brown haloes around the inked lines. “B. Franklin’s New Ink,” “written Aug. 3, 1731” and noted to be “pale when first wrote” has probably aged the best.

Iron gall ink was used in quill pens, so it had to flow and then dry. A completely different type of ink was developed for printing.

TOMORROW: Printers’ ink.

No comments:

Post a Comment